TORONTO -- Ontario will appoint an independent third party to review how watered down chemotherapy drugs were given to more than 1,100 patients, some for as long as a year, Premier Kathleen Wynne said Thursday.

"It's unacceptable that this should have happened, that the doses would not have been accurate," said Wynne at the opening of a new breast cancer centre at Toronto's Sunnybrook hospital.

"The minister is pulling together all of the people who are necessary to figure out what happened, to get to the bottom of it, to understand how this happened and whether there's something systematic that needs to be addressed."

Many hospitals mix the medications themselves, but four hospitals in Ontario and one in New Brunswick all used the same supplier based in Hamilton, Ont. to prepare the drugs.

There was too much saline added to the bags containing the chemotherapy medications, in effect watering down the prescribed drug concentrations by three per cent to 20 per cent.

The five hospitals are contacting affected patients to arrange quick appointments with their oncologists. Family members of Ontario patients who died are also being contacted.

Health Canada, the provincial governments, Cancer Care Ontario and the Ontario College of Pharmacists, are investigating. The hospitals are also conducting their own probes.

Dr. Carol Sawka, a spokeswoman for Cancer Care Ontario and an oncologist of 25 years, said she's never seen anything like this before.

"This is an uncommon situation that has occurred on a backdrop of what's fundamentally a very safe and high-quality system," she said.

There are 77 hospitals who provide chemotherapy in Ontario, Sawka said. Almost all of the other unaffected hospitals have said they haven't used the drug mixtures from Marchese.

Since hospitals buy the drugs, Cancer Care Ontario doesn't know how many of them mix the drugs themselves or have it done off site, she said.

All five hospitals have stopped using the drug supply. Saint John Regional Hospital in New Brunswick is now mixing its own.

The third-party review will try to determine if the problem is systemic or just an isolated incident, said Health Minister Deb Matthews.

Asked whether the privatization of the preparation of chemo drugs was a factor, Matthews said "that's an important question."

"I don't want to speculate too much, but I know that cost is not likely," she said. "But that is a question."

The supplier, Marchese Hospital Solutions, said suggested that the problem wasn't how the drugs were prepared, but how they were administered at the hospitals.

The concerns are the result of "a difference between the manner of administration used in some hospitals that was not aligned with how the standardized preparation has been contractually specified," the company said in a statement posted on its website.

The medication wasn't "defective," it said. "We are confident that we fully met all of the contract requirements including both volume and concentrations for these solutions."

But questions have been raised about how the lower-than-intended doses of the drugs might have affected patients and whether or not those who have died could have lived longer with proper doses.

"It's really impossible for me to speculate about the outcomes of 990 patients that I've never met, because each person's care is unique," said Sawka.

But in some cases, the watered down drugs would have been one of many chemo drugs that the patient was taking as part of their treatment and may not have affected their prognosis, she said.

"Our concern is that we get those answers, that we find out what happened and we have the right people investigating that, and that the individual patients get the care that they want," said Wynne, who was joined by her partner Jane Rounthwaite, who was treated for breast cancer a few months ago.

"That's where my heart is, is with those individuals who are frightened and they need to talk to their oncologists."

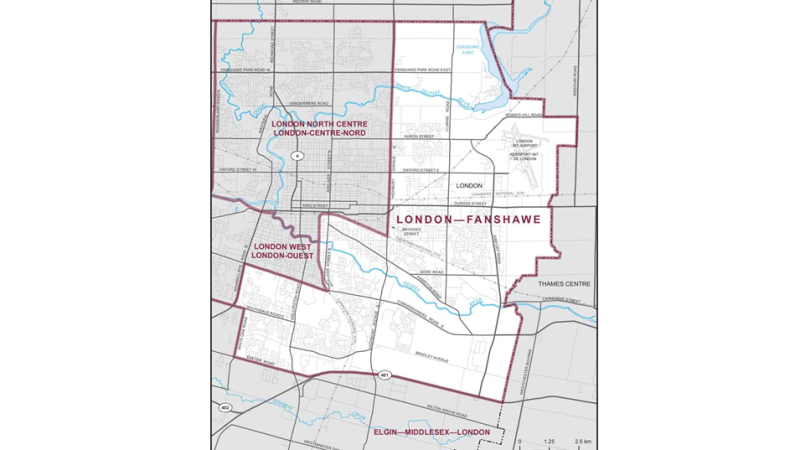

The underdosing affected 665 patients at London Health Sciences Centre, 290 patients at Windsor Regional Hospital, 34 at Lakeridge Health in Oshawa, one patient at Peterborough Regional Health Centre and 186 patients at Saint John Regional Hospital.