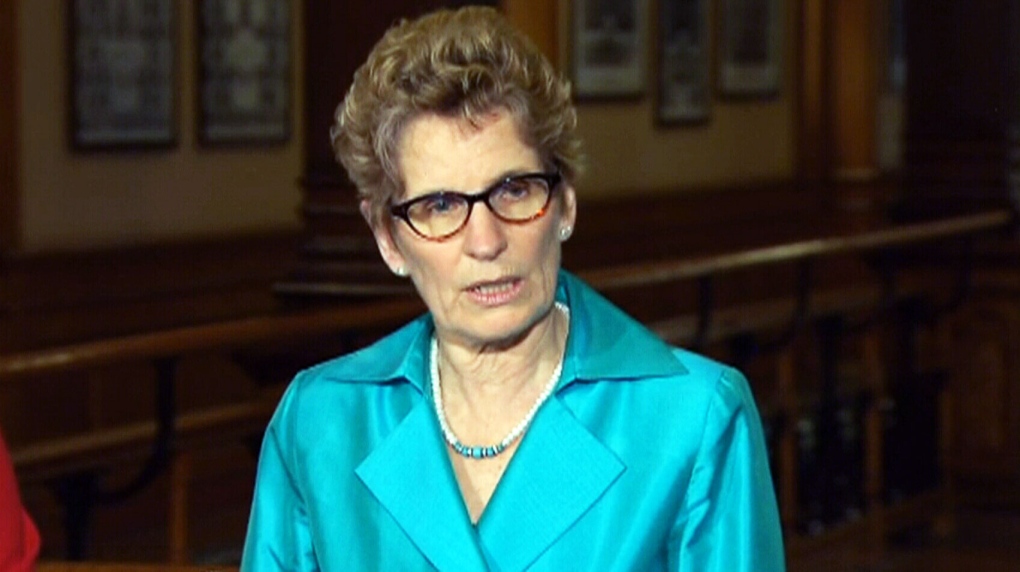

TORONTO -- Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne vowed Thursday to rectify the problems that led to diluted chemotherapy drugs being administered to cancer patients in two provinces, but she won't tell Ontario hospitals to go back to mixing their own medications.

There is a gap in oversight of companies like Marchese Hospital Solutions, which was contracted to prepare the cancer drugs for four hospitals in Ontario and one in New Brunswick, she acknowledged.

Health Canada and the Ontario College of Pharmacists are working to close that gap, and the college is willing to provide oversight of new compounding facilities like Marchese, she said.

"But I really believe that it's not the time for finger pointing," Wynne said.

The college already oversees pharmacists, including those who may have worked for Marchese, but their powers could be expanded to give them complete authority over the facility.

It was a jurisdictional grey area, with both the college and Health Canada unable to agree on who was responsible for the facility.

Health Canada argued that if Marchese was doing something that was usually done in hospital -- like mixing drugs -- that would fall under provincial jurisdiction.

"There are lots of people who have a piece of the oversight pie," said Ontario Health Minister Deb Matthews.

The crisis has also raised questions about whether the privatization of health care has gone too far.

The bags containing the chemotherapy drugs were filled with too much saline, watering down the medication by as much as 20 per cent. Some patients received the drugs for as long as a year.

It's a grave warning that privatization has to stop, said New Democrat health critic France Gelinas.

"As those new companies spring up all over to do for-profit services for hospitals, the government basically stayed asleep at the switch," she said.

"They never looked at who was picking up this work to make sure that the level of oversight, the level of quality assurance that we had before were being transferred over. The work got transferred, the oversight did not."

But the fact that the problem surfaced only where the mixing had been contracted out by the hospitals may not be the problem, Wynne said.

"I'm not going to make that cause-and-effect link, I think that's what the review needs to do," she said.

The province has asked all 77 hospitals that provide chemotherapy to check and make sure they didn't receive diluted drugs and 69 have responded, said Matthews.

Ontario has an excellent health-care system, but it's not perfect, Wynne said. When problems crop up, the government will fix it so that it doesn't happen again, she said.

A pharmacy expert, Jake Thiessen, will review the province's cancer drug system, Matthews said. A working group that includes doctors, Cancer Care Ontario, Health Canada and others are also looking at the problem.

Federal Health Minister Leona Aglukkaq said in a letter to Matthews on Thursday that she has instructed Health Canada officials to co-operate fully with the investigation.

"I was deeply upset to learn that more than 1,000 cancer patients apparently received incorrect dosages of medication," the letter said.

Matthews said she has told those looking into the matter that this is not a time for "finger pointing."

"I want all of us collectively to do what's best for patients," she said.

But it is the time for finger pointing, said Progressive Conservative Lisa MacLeod.

Once again, the governing Liberals are trying to wash their hands of another health-care fiasco, she said.

The drug scare follows two spending scandals at eHealth Ontario, the agency tasked with providing electronic medical health records, and Ornge, the province's troubled air ambulance system -- both of which the government failed to oversee, she said.

"The government needs to start preventing these problems," MacLeod said.

"It's as if every time another crisis happens, Deb Matthews calls an oopsie. Oops, I've done it again. And it's going to be OK, but don't point your fingers at me."