EINDHOVEN, Netherlands -- The war in Europe didn't end with a decisive, Hollywood-style battle for soldiers such as Al Stapleton and William Stoker, or for sailors like Cyril Roach.

It just petered out.

Stoker, a former private with the Seaforth Highlanders and later a military policeman, was content for a few days to enjoy the victory party that seemed to go on forever in Amsterdam.

"We had a marvellous time. You couldn't have had a better reception," said Stoker, who now lives in Peterborough, Ont.

"I felt relief. I was only 18, pretending to be 19."

And when the overwhelming tides of celebration, which began 70 years ago Friday, finally began to recede, they -- along with hundreds of thousands of other Canadian servicemen and women -- were left with one inevitable, stark question: what now?

They had survived the greatest conflict in human history, one that would reach a final, terrible conclusion with the dropping of the atomic bombs and the surrender of Japan a few months later in August 1945.

None of them knew at the time how quickly the war in the Pacific would unravel, but with victory over Nazi Germany, the survivors began to think of something they'd dared not consider until that moment.

What were they going to do with the rest of their lives?

It is easy to forget amid the sentimental haze of anniversary celebrations washing over Canada, the U.S. and Europe this week just how tentatively these stooped, silver-haired heroes stepped into the new world.

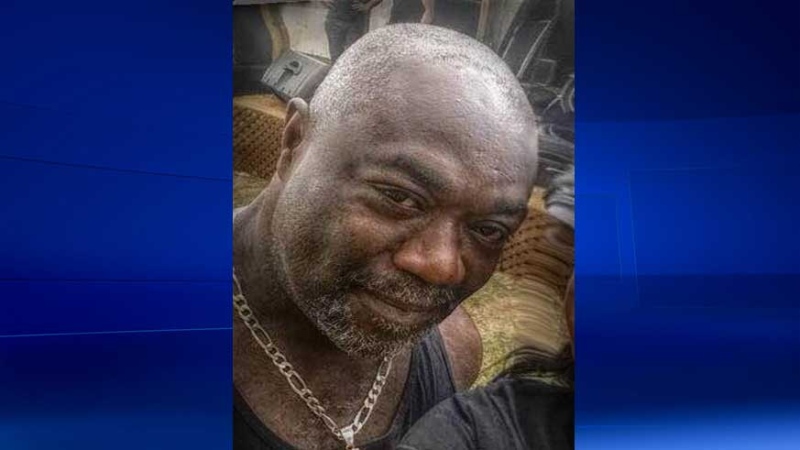

Stapleton, now 93, said at the time he didn't have a clue what he would do when the war ended. It took a year or so to find some direction, which only came after he returned to the comforting, familiar surroundings of the family home in southwestern Ontario.

Lost today is not only the confusion of the time, but the simmering anger felt by some troops that the war had not ended sooner, especially those who fought the final desperate battles in places like Leer, Germany.

The way the army and the Canadian government organized the repatriation got under Stapleton's skin. As he boarded the boat to come home, he was seated next to some guys who -- in the case of conscripts -- had only been overseas a few months, or a few years for volunteers with the units that followed his 1st Canadian Division.

"There you were, five and a half years, and being treated exactly the same way," he said.

He was honourably discharged in August 1945, and never looked back. Unlike others who made a career out of the army, or those like that returned for Korea, like Stoker, Stapleton was happy to shed his uniform and never march again.

Five and a half years away from home. "If you have to, you have to," he said with a shrug.

Going home felt pretty strange. On the train ride to his parents house, he marvelled at how the rolling farmland of southern Ontario had been paved over and industrialized by the war.

His world, the one he grew up in, was largely gone.

That kind of lament is seldom heard amid the din of victory parades, prayers and the pontification of leaders and generals who talk of the sacrifices of the war generation, many members of which are stepping into the mist of history.

Cyril Roach, who helped navigate a Royal Navy tank landing ship to Juno Beach and later helped reinforce those same Canadian troops fighting in the boggy Scheldt estuary, longs for the solitary and sense of purpose from that time.

He remembered the tired, perpetually soaked infantry, whom British Gen. Bernard Montgomery christened the "Water Rats," a play on the infamous British desert rats of the North African campaign. Those Scheldt battles cost the First Canadian Army some 6,367 lives in what Canadian Press war correspondent Ross Munro described as the most miserable fighting of the European campaign.

"Canadians and British served together. We were a team," Roach said in a recent interview. "We didn't separate ourselves."

His landing ship took off for Pacific as the war in Europe drew to a close and Roach found himself landing troops on the Malaysian peninsula, in Singapore and in Hong Kong before Japan finally surrendered.

He was demobilized back in Britain in 1946; 90 days afterward he was in Canada, where he's remained.

Stoker went to university after the war, but ended up back in uniform in the early 1950s at the outbreak of the war in Korea. Stapleton, too, went to school and became a broadcast technician at the CBC, where he spent his entire career.

"You have to make a life for yourself," Stapleton said.

"I didn't do too bad. On a day-to-day basis, I don't think about (the war) too much. That's looking back and it doesn't get you too far."

What stays with him is the suffering of the people of Europe, particularly those in southern Italy, where people were near starvation because of the collapse of the local economy. The allied strategy of bombing railheads to rubble virtually strangled commerce in the area.

"A lot of people want don't remember that," Stapleton said. "They'd prefer to forget."