LONDON, ONT. -- There is a murder spree raging across Canada.

Serial killers and psychopaths are running up the body count while pursued by a legion of police inspectors, private detectives, crime reporters and lawyers.

The writers who generate these tales of criminal terror - and the book buyers who can’t wait to read them - share an admitted attraction to the dark side. From traditional detective novels to police procedurals, and outright noir, they are drawn to humanity’s less sunny side.

According to the Canadian Book Market report, in 2018 the thriller category accounted for $73-million in sales, while mystery books claimed another $26-million.

That’s a combined market of almost $100 million – about nine per cent of all book sales - for the murderers and their pursuers to play in. Small wonder perhaps that the hit men just keep coming.

But the writers who craft these stories are not just in it for fame and fortune.

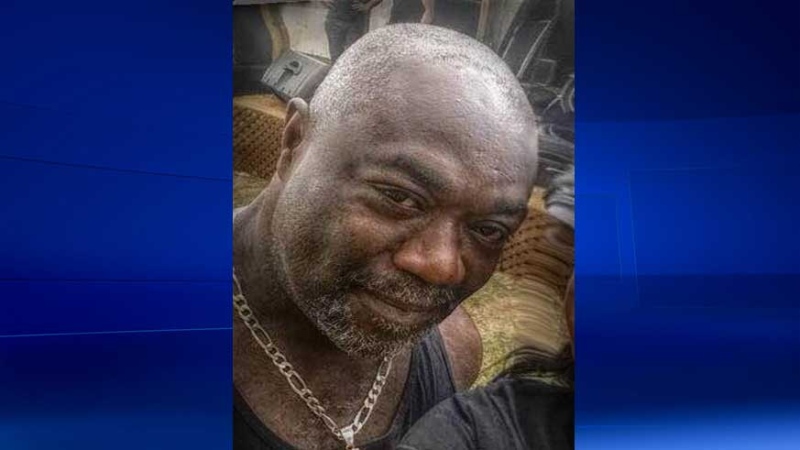

Desmond Ryan writes a series based on his police detective character Mike O’Shea, set in Toronto. He offers a simple explanation for why a retired police detective like himself turned to crime fiction.

“I could have written true crime, but that’s a lot of work, making sure all of the details are correct and all of that. Crime fiction is a lot more fun.”

And fun seems to be the motive behind all the killings. “I think crime fiction is fun,” says Lynn McPherson, a crime writer who also acts as the Southern Ontario representative for the Crime Writers of Canada.

She rejects suggestions that crime fiction came be dismissed because it is formulaic, pointing out that the crime or mystery sets parameters, within which lies a world of possibilities.

“A good crime fiction writer has the same challenge as any other author – to write a compelling story that readers enjoy.”

The stories are plot driven, she says, but second to the plot comes the characters, and even the heroes in these twilight tales are haunted souls.

And the criminal mayhem is happening from coast to coast to coast.

In B.C., Sam Weibe examines the underbelly of Vancouver while R. M. Greenaway explores the isolated northern interior.

On the prairies, Anthony Bidulka writes about Saskatoon, while Garry Ryan explores Calgary.

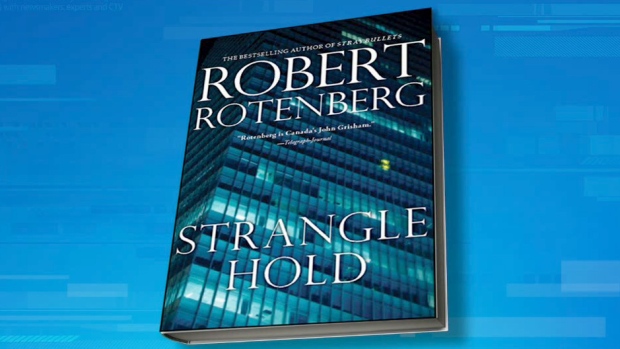

Ontario has Robert Rotenberg’s Inspector Ari Greene keeping Toronto safe while Ottawa’s Inspector Michael Green is deployed by Barbara Fradkin.

And a current favourite is Giles Blunt’s John Cardinal series, the subject of a popular television adaptation airing on CTV.

Quebec’s Eastern Townships are patrolled by Louise Penny’s Inspector Gamache of the Surete, and John Farrow’s Emile Cinq-Mars maintains order in Montreal.

Atlantic Canada has its own crime writers including Phonse Jessom who has launched a noir series on an outlaw biker turned cop, and Anne Emery helps keep a lid on Halifax.

Kevin Major is providing order on the Rock, and there is even a Yukon element with the stories of Kelley Armstrong.

And this is just a random sampling. A complete list is beyond the scope of this article.

Michael Arntfield is an associate professor in the English Faculty at Western University and teaches a creative writing course focused on crime fiction.

He says the best crime writing tends to come from people who know what they are talking about. “The best police procedural writers tend to be crime reporters, cops, or even former criminals, like James Ellroy, who have firsthand experience” he says.

Michael Arntfield speaks in this file photo.

And Arntfield knows what he is talking about. This former police detective has been on the front lines himself. His own book, Murder in Plain English, is used as a textbook in his class and examines the ways in which crime fiction and actual crime intersect, and sometimes inspire each other.

“In general, realism and resolution are what readers want and are the hallmarks of a compelling and usually commercially successful work."

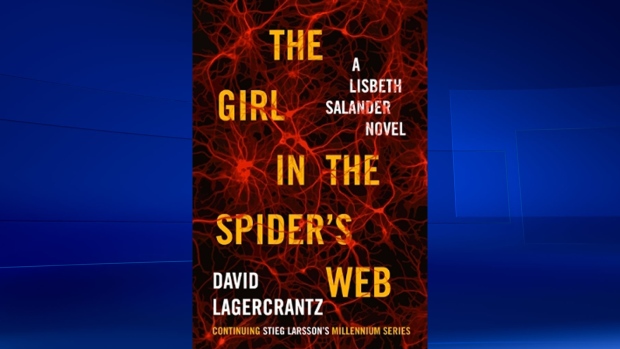

Canadian crime fiction can be neatly fit into a larger global resurgence of the genre, which many attribute to the enthusiasm created by Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

The book and its two sequels were so successful that an entire sub-genre of Nordic Noir was launched and continues to prosper today.

The Girl in the Spider's Web is the first sequel to Stieg Larsson's best-selling crime trilogy.

Like the Scandanavian writers, Canadian authors can make use of environment and isolation to give their mysteries a bleaker, more gothic tone.

But if the current craze was launched by Larsson’s work, which was only published after his death, how long can it be expected to continue?

Arntfield has an answer for that.

His studies of the genre lead him to believe that crime fiction thrives amid certain realities: “the conditions appear to be political upheaval with a focus on individualism, economic stability, and an average or lower-than-average real violent crime rate.”

So as long as times are good the demand for crime fiction seems secure.

But if the economy falters or the crime rate rises in the society, then “true crime as a voyeuristic indulgence is no longer marketable.”

Arntfield has, in fact, detected four historical waves of rising and falling popularity of the genre.

So for now, you can expect Canadian readers to continue spending their millions, and the crime wave will continue.