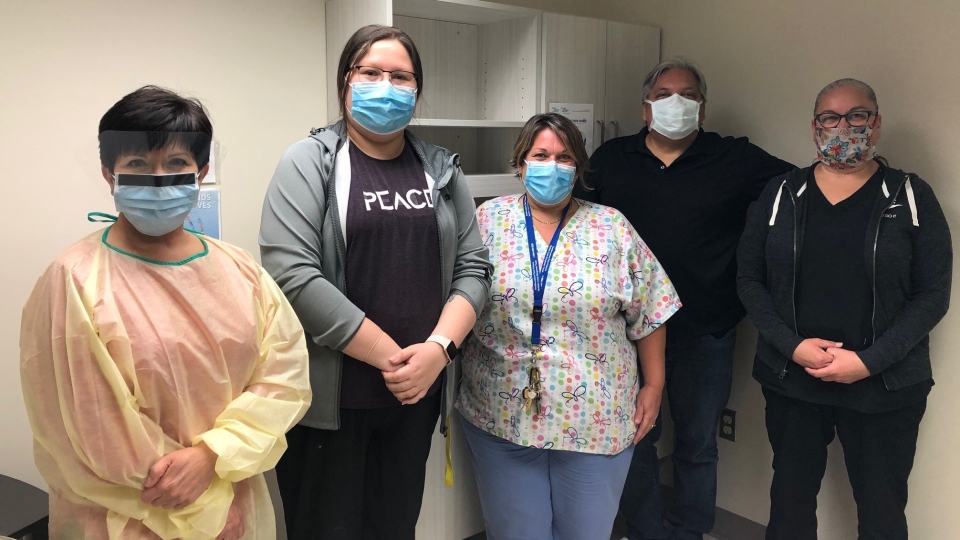

KETTLE AND STONY POINT FIRST NATION, ONT. -- The First Nation community near Sarnia, Ont., has opened a COVID-19 assessment clinic, located at the Kettle and Stony Point Health Centre.

Before the COVID-19 assessment centre opened locals would have to travel approximately 45 minutes to the nearest city to get tested.

The overall goal of the clinic is to test more people and to reduce the need to travel.

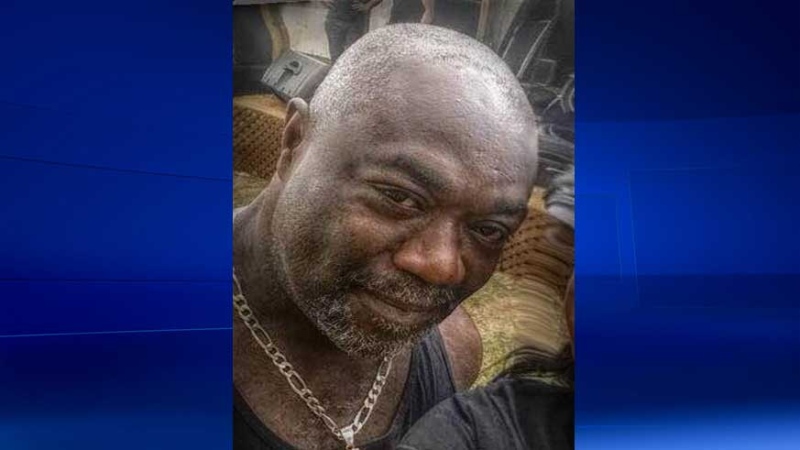

“First Nations have a long-standing difficulty with access to health care,” says Kettle and Stony Point First Nation Chief Jason Henry. “[There are] many underlying issues, and with COVID-19 we are a high-risk demographic of potentially having death from COVID-19, so bringing [tests] closer to the community is best for everybody.”

A person who is experiencing COVID-19 symptoms has to be referred by a doctor in order to make an appointment at the health services centre, then they can get swabbed by a nurse.

Community health nurse, Carlene Mennen, says the facility has been changed in order to accommodate people who are waiting for a COVID-19 test.

“We have a separate waiting room for them, we’ve marked the doors to reflect that. Over the phone they will be given instructions once they arrive to go to waiting room two. There they will be screened further…then they will join me in an exam room where myself or another nurse will conduct the test.”

The clinic is in partnership with Lambton Public Health and Bluewater Health.

“If somebody tested positive their test results would go to Lambton Health Unit,” says Mennen, “it takes anywhere from 24 hours to five days for a test result to come back.”

The medical officer of health would then notify the individual of the positive test, and the health unit will follow up with contact tracing.

There are about 1,000 people living on the reserve as of today. So far, three cases have been confirmed on the reserve, all of whom have recovered.

Henry says he is very proud of the clinic and hopes that it will help to contain the virus, and potentially build a stronger relationship between communities.

“In a global pandemic, it’s not the time to draw jurisdictional lines in the sand, it’s not the time to put bipartisan lines in the sand, it’s time to work together, work collaboratively and move beyond those historical divides we’ve had in Canada,” he says.

The First Nation has been in a state of emergency since mid-March, when its borders were closed to visitors and first responders were enlisted to operate a screening checkpoint at the community entrance.

For six weeks, staff and volunteers have been delivering community care packages and food to vulnerable members of the First Nation, living both on and off reserve.