Ontario Provincial Police say they've undergone a "massive" shift in their approach to overdoses as the opioid crisis deepens.

The changes include investigating every overdose call, giving officers access to real-time data on overdoses, and employing new software to look for links between separate cases in an effort to track down those dealing deadly drugs.

"We're changing the way we do business, how we look at overdoses and how we investigate them," said Supt. Bryan McKillop, the head of the force's opioid working group. "This is a massive change for us."

The shift in the force's approach comes as it said this week that overdose deaths in its jurisdictions are up 35 per cent in the first quarter of this year compared to the same time last year.

The latest available federal data shows more than 1,200 Ontarians and nearly 4,000 Canadians died of opioid overdoses in 2017.

The OPP -- which covers 340 of Ontario's 440 municipalities -- began its work to improve data collection and analysis about a year and a half ago in an effort to capture overdose statistics that weren't easily accessible, McKillop said.

The force updated its internal databases so that overdose data can be analyzed at any time, by any officer, in any part of the province.

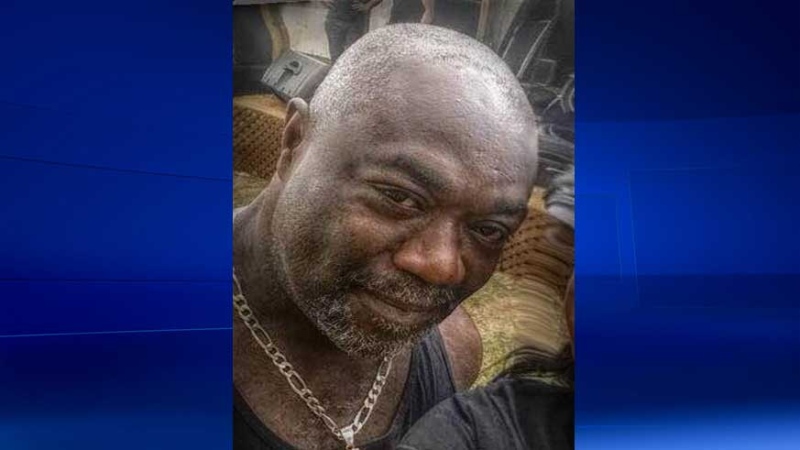

A recent report on the latest figures shows 75 per cent of fatal opioid-related overdoses since 2016 were men with an average age of 41. The balance were women with an average age of 46.

The opioid problem also seems to be hitting the province harder in central and west regions.

To deal with the issue, officers have been carrying the opioid antidote naloxone since September 2017, administering it 79 times -- 73 lives were saved as a result, the report said.

Key among the changes the force has made as it benefits from more data is that every single overdose call -- fatal or not -- is investigated.

"No longer would we go to the scene and the ambulance says 'we got the person, we don't need your help,"' McKillop said.

Police would previously mark those incidents in their reports as an "ambulance" call or a "medical assist" call and move on, recording little other information. Officers now follow up with overdose victims and gather basic information, especially about where the drugs were bought, McKillop said.

That data can be used to help find connections to drug dealers, he said.

If police can find the dealers and have enough evidences, serious charges can be laid.

The force has laid 10 manslaughter charges against alleged opioid dealers since 2016. In one case, the manslaughter charge was withdrawn after a dealer pleaded guilty to criminal negligence causing death and was sentenced to 2.5 years in prison, said spokeswoman Staff Sgt. Carolle Dionne.

The OPP is also improving its ability to test for opioids when responding to overdose calls.

It has bought a dozen ion-mobility spectrometry devices that have been placed strategically throughout the province. The machines can quickly determine the composition of drugs, helping police warn the public if a batch of cocaine or heroin, for example, could be tainted with fentanyl.

The devices can be moved around the province should data show overdose hotspots, McKillop explained, adding that there are plans to buy more.

"We can now figure out what substance we're dealing with in a way we've never been able to do before," he said.

The force's overall shift was the brainchild of former commissioner Vince Hawkes, who retired last November, McKillop said. Much of it is based on the 2017 federal Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act, which enables people to call for help in an overdose situation without fear of being charged.

McKillop also said the force's data on opioids will not be held under lock and key.

"This information is available to anyone who asks," he said. "Informed decisions are almost always made through data."