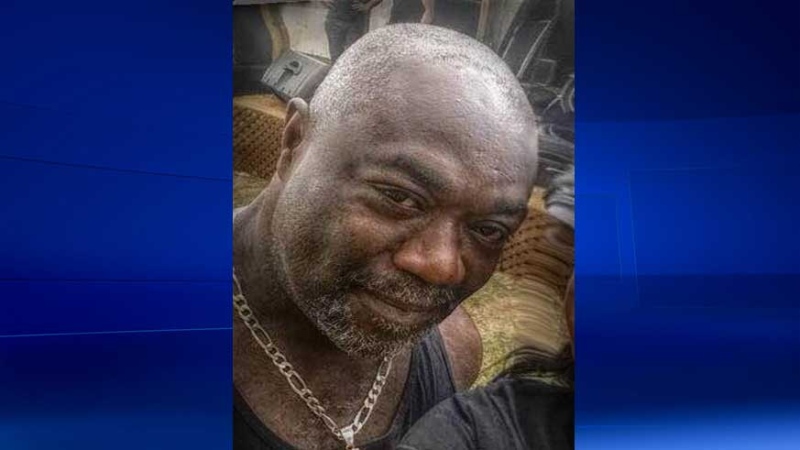

The father of a terrorist sympathizer who died in a confrontation with RCMP Wednesday says Aaron Driver was a troubled child, but appeared to have turned his life around after converting to Islam.

Wayne Driver said his son Aaron Driver stopped doing drugs, had a full-time job, a girlfriend and was civil again after years of problems that began when his mother died when the youngster was seven.

But then the father said CSIS contacted him in January 2015 about disturbing posts his son had made on social media.

"It was babies in mass graves and killings of other Christians, and he said that they had it coming to them and they deserved it," the father said in a phone interview from his church in Cold Lake, where he retired from the military and is training to be a pastor.

When Wayne Driver was told his 24-year-old son had died in Strathroy after allegedly making a martyrdom video that suggested he was planning to detonate a homemade bomb in an urban centre, the father said it came as a "surprise that he'd actually gone that far."

His son's troubles started when his mom died of brain cancer, Wayne Driver said. The son blamed the father.

Wayne Driver remarried when his son was eight, but the boy wouldn't accept his stepmother. He refused to participate in counselling and at one point, he stopped eating.

"He was saving his lunches at school in the locker. His teachers found out that he was doing that because his locker started to smell," his father said.

"He was taking his lunches to school and not eating them because he wanted to die to be with his mum."

Wayne Driver and his wife were both in the military. At 15, Aaron Driver ran away right before they were supposed to be transferred from Edmonton to London, Ont.

At 16, he applied to be emancipated and his father agreed to sign the papers. The teen lived in a youth home in Ontario until he was 18, and when Wayne Driver went to visit, his son would often refuse to see him.

When Aaron Driver was 21, he came back to live with his father and stepmother when they were in Winnipeg.

"He said he had converted to Islam. It's not my belief, of course, and I just figured it was a phase he was going through. But we supported him because it had changed his life," Wayne Driver said.

"We still tried talking with him about Christianity. But he wouldn't hear anything of it."

The family was transferred to Cold Lake, but the young man stayed in Winnipeg. He'd quit school because of trouble with math, his father said, but was planning to return.

Then communication became strained again. Most of the news his father got about his son came from his stepsiblings.

Aaron Driver was picked up by police in Winnipeg in June 2015. RCMP say a raid on his home found a recipe for homemade explosive devices on his computer.

Police also say Aaron Driver was communicating with well-known members of ISIL.

Aaron Driver was held on a peace bond due to fears he would "participate in or contribute to, directly or indirectly, the activity of a terrorist group to facilitate or carry out a terrorist activity." He was released under a raft of conditions in February.

Amarnath Amarasingam, an expert on radicalization who has spoken on multiple occasions with Aaron Driver, said the young man was radicalized while looking for order in a life that was characterized by chaos.

Amarasingam is working on a study at the University of Waterloo, interviewing western foreign fighters and people who have been radicalized in Canada. He said he was brought in by Aaron Driver's lawyers.

"He was a very troubled guy. He'd gone through several tragedies in his life," Amarasingam said.

On top of losing his mother, Amarasingam said the Aaron Driver's girlfriend was pregnant at 16, but lost the baby and one of his friends was fatally shot in London, Ont.

Amarasingam said he had last heard from the young man in April.

"He was saying that he had a job, he was working, he had a group of friends, he was moving on with his life," he said.

But between April and August, there were a number of attacks on Islamic countries during Ramadan, Amarasingam said. This helped "crystalize" Aaron Driver's allegiance to ISIL.

Wayne Driver said he never stopped trying to reach out to his son.

"I called him a month ago. I said, 'Hi, how are you doing?' He said, 'I'm not talking to you,' and he hung up the phone on me," Wayne Driver said.

"So I tried reaching out again, I tried sending texts, he wouldn't respond to texts. He unfriended me on Facebook."

He said prayer is helping him get through his son's death.

"It would be very difficult for sure if I didn't have God's love on my side."