He was a leader in the Forest City faith community — the pastor of Metropolitan United Church, one of Canada’s leading Protestant denominations.

He was a man who dedicated himself to his faith in Jesus and his service to his congregation. And then he wasn’t

Bob Ripley left religion and became an avowed atheist, a non-believer. He began living what he calls a “life beyond belief.”

It was an exercise in adopting an entirely new identity.

As the reverend of Metropolitan United, the life of the church defined who Ripley was in his own mind.

“My calling to ministry was so all-encompassing that my beliefs had a huge impact on who I was as a person,” he said. “I was happy in that life and happy to be known as ‘the reverend.’”

Unlike many others who experienced de-conversion, Ripley does not describe a story of breaking free from the shackles of more fundamentalist or conservative denominations.

“While I may think of my deconversion as a liberation of sorts, I never felt my religious identity was oppressive,” said Ripley.

Perhaps reflecting the very liberality of the United Church itself, Ripley expressed no resentment or hostility towards his former faith.

Instead, he described a change of perspective. “I simply feel that I’m now seeing life as it is and not as I would want it to be.”

And it seems Ripley is not the only person undertaking this change.

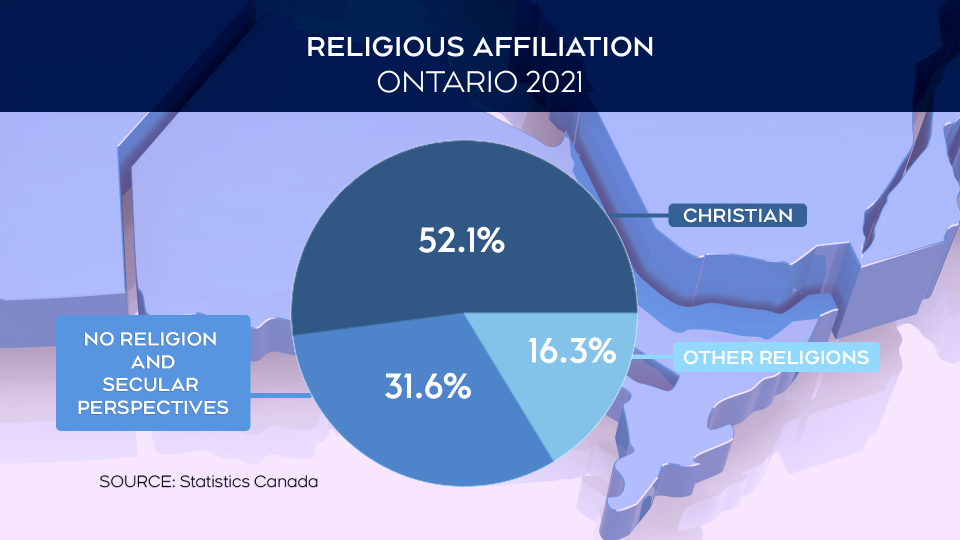

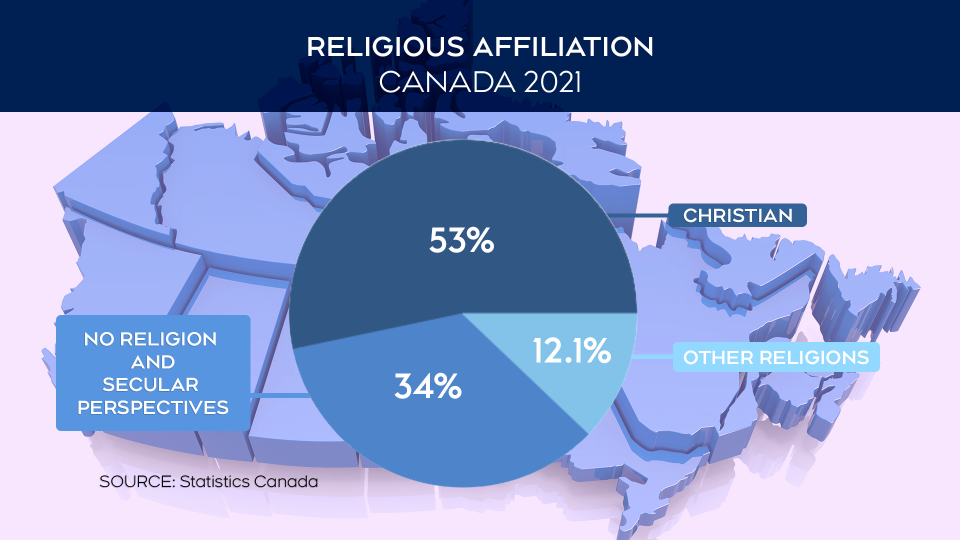

According to Statistics Canada, in the decade between 2011 and 2021, the share of Canadians identifying themselves as Christian dropped 14 per cent to just 53.3 per cent of the population.

During the past two decades, Canadians having no religious affiliation more than doubled to 34.6 per cent.

In our current moment, only half of Canadians are Christian, and a third have no declared religion at all. That leaves just 12 per cent for all other faiths combined.

One of the perplexing aspects of Ripley’s rather public change of identity is the fact that so few people have chosen to engage in a discussion of his de-conversion.

“I’ve often speculated on why that is. Are they uneasy with the idea of someone in a high profile position such as I held changing their mind?” he questioned.

Or is it something more specific? An unwillingness to confront the questions that redefined Ripley’s identity.

“I found it particularly odd that few of my former clergy colleagues wanted to engage with me to point out the error of my ways and call me back to faith,” leaving him to wonder “Do they secretly harbour similar doubts but are unwilling or unable to follow where they lead?”

For himself, Ripley described the transition as a sort of investigation of the world around him, and an energizing experience.

“Emotionally, it was an exciting time as I applied logic and reason to both the doctrines of Christianity in particular and world religions in general,” he said.

Many fundamentalist Christians reject the role of the church as mediator between the faithful and God, and describe the religious experience as having a personal relationship with Jesus.

For Bob Ripley, the act of walking away from belief was “like finding a personal relationship with reality.”